I often think about funeral speeches. Those that have moved me with their love, humanity and individuality; those that have disappointed with their stock phrases and easy platitudes. In moments of anxiety for the safety of people I love, catastrophising, I sometimes wonder what I might say about them. It’s unthinkable to contemplate their demise, but there’s some comfort in the public affirmation of someone’s importance, their centrality. Stop all the clocks.

Death in a pandemic snatches these rites away and leaves us hanging. In a way the clocks did stop when my father died — all those calendars still on March’s page even as the summer started to fade. But a death in a pandemic cannot be marked and mourned in our tried and tested ways.

When it happened, on March 10th, we were still out and about, nervously; all washing our hands to Happy Birthday twice, the chorus to Mr Brightside, or, in my mother’s case, An Irish Airman Foresees his Death.

We thought we might have a funeral if we moved quickly, though we wondered whether many would come; my mother wanted to do him proud. A Post Mortem and a wait for the Coroner’s report delayed our plans, and the country began to shut down. We pinned our hopes on a summer gathering on his birthday, instead of a funeral; told ourselves it would actually be better that way. We’ll do him proud, in August. For now, a simple cremation, standard gown rather than own clothes, splash the money on a big party later, says my mother.

Registry offices had not yet closed their doors to Covid, but I had to go alone. There’s a family group waiting for a wedding, cheery, daft, fun — and me: “I’ve got an appointment to register a death.” Buzzkill. I feel bad for them.

I photograph the waiting room on my phone, bit strange in the circumstances, I get looks, but it’s what I know how to do. It distances you, allows you to process it later. And I want to remember the details, fix them, mark the moment. Stop the clocks.

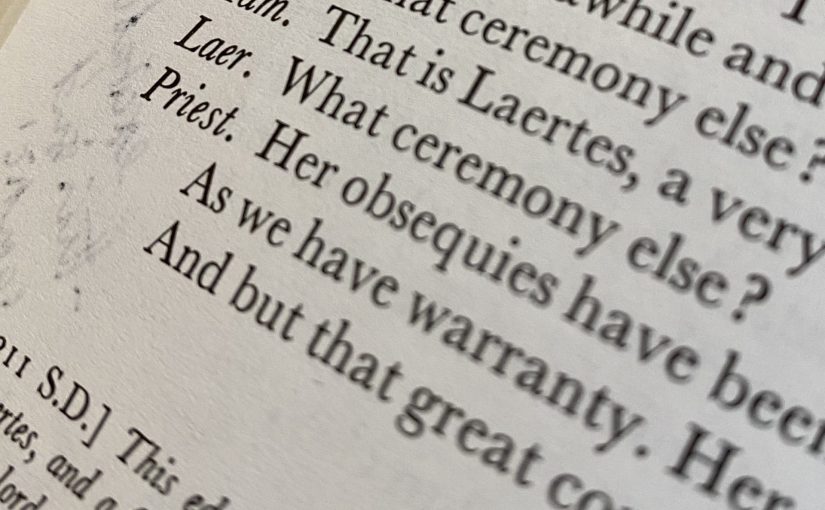

In the room, and the registrar snips the corner off my dad’s passport without so much as a by-your-leave. It seems so perfunctory for such a symbolic act. ‘What ceremony else?’ pops into my head, and not for the last time.

A few days later, my parents’ cat Treacle, already on borrowed time, finally ends her days at the vet’s. We send her off for cremation. She can go in the river with my dad when the time comes.

I’d not wanted my last image of my dad to be a vision of that hospital aftermath. So I arrange a visit to the funeral home. It’s not a Covid death so it’s still permitted. Four of us go. I don’t regret it, but I don’t like it either. Features glossy, unnatural. Revolting shiny gown. Platitudinous tripe masquerading as poetry, despite our writing ‘no religion’ on the form. No, really, God did not ‘look down and see that he was tired’. He was stolen from us much too early, at what should have been the start of a new lease of life. The assumptions make me angry, as does the tacky font and sentimental artwork, although the funeral director is kind and says all the right things.

Mum does not mind this — she doesn’t notice the paraphernalia, only Dave, and not the Dave who’s lying there. She wants me to take a photograph. Can’t do it. Finally I manage her hands on his, iPhone death photo, in a gentle, soft monochrome. It’s quite nice actually. It turns out to be a comfort, later, and though I still hate the gown, at least it has simplicity.

Covid means we can’t all go in together. Dementia means we can’t be apart. I end up accompanying everyone in turn.

I get on with the death-admin while we wait for Cremation Day.

My parents’ neighbours in the street turn out to applaud the funeral cortège as we inch down the road. Brother fixes a stereo onto his car roof to play “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” as we go. Is it tacky, asks my mother — the neighbours say it’s just the mood we all need and it suits my father’s mischievous sense of humour. It’s quite a popular choice for funerals, I am told. So I’m laughing, crying, listening to the applause, and I love the man with his town crier’s bell and the woman who holds up framed photographs of my dad’s that she’d bought at an exhibition. Everyone outside their front doors, it’s powerful, and I’m still grateful. We think about the ways we’re having to reinvent and repurpose rituals, wonder whether this is permanent.

We are eight, at the crematorium, almost outnumbered by the staff. No celebrant, didn’t see the point. It is forbidden to touch the coffin. Tubular Bells, an old favourite of his, is playing over the PA system. Who the hell plays the music from The Exorcist at a funeral? Answer: David’s children. Socially distanced, we sit there for a bit, laugh, chat, tell a few stories, and then we say sod this, let’s go and have a drink. Bye, Dave.

It is not enough.

For a while we still kid ourselves there will be a party on his birthday in August. That we can have a drink with family, neighbours and friends, say what we want to say, be heard, stop the clocks.

But we know it can’t happen, and it doesn’t.

I order a water-soluble urn and wonder if both Dave and the cat will fit inside. Will we need a funnel? Dave or Treacle in first? What if there is overspill? Will we fall in the water tying the urn to the landing stage? The urn arrives and the children say it looks like something out of Horrible Histories. They’re right.

In the end none of us can bear to put him in the river and have him washed away. Mum wants him in the garden where she can talk to him, round the bottom of a standard box tree. But now we don’t have a suitable container — just the ashes in a bag in a box from the Mid Counties Co-op and it looks like a great sack of flour. Can we scatter from that? Will it make a mess? What else can we use? A bucket? A bowl? A film developing tank? Cocktail shaker, ice bucket? It’s a bleakly amusing kind of improvisation.

We decide that bag, box, trowel will have to do. Cat goes in first; she has a proper scatter-box; mum makes her a speech. We FaceTime my brother in Glasgow and in the end mum simply tips the ashes in over the little box hedge, no trowel. She leans right over, gets her hands involved, stirs the pair of them up together in the soil, then dumps half a bag of compost on the top in case a breeze gets up in the night. It’s Dave and Treacle’s spot now. Mum says we can do what we like with her when the time comes but she’d quite like to join them there if that’s ok. Fingers crossed the little tree stays healthy.

We need a drink after that. But the day’s finale is yet to come. Pools of foul water start oozing from the drain and before we know it the floor is covered in an evil-smelling sludge. We try and we fail to unblock the ancient waste pipe behind the washing machine. And this is how life goes on, and has gone on since. The everyday inconveniences, the minor and the major catastrophes — they don’t pause for the big emotions. The clocks don’t stop after all.

What ceremony else?

Maybe next year. Mum says we might have missed the moment. I hope she’s wrong.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.